The first workshop in this program of three, focusing on Armenians and Jews in the Diaspora at the time of empires, took place on 18 November 2022 at the École Française d’Athènes. Scholars from Greece, Austria, France, Italy and the United States joined at 6 Didotou Street in order to present their research to the public. The event was open to a wider audience thanks to a zoom connection. Each presentation could last up to 25 minutes. After each panel, a wider discussion took place. The general atmosphere was agreeable and collegial. Speakers engaged with each other and this was very promising for the coherence of the final volume to be published at the end of our research program. Our meeting articulated French and English in a fluid way, with no excessive formalism. This proved successful an arrangement.

Hervé Georgelin [1], Assistant Professor at the Department of Turkish Studies of the National and Capodistrian University of Athens and Odette Varon-Vassard [2], partner of the Jewish Museum of Greece and former faculty member at the Hellenic Open University, have designed the research program (to be consulted as an attachment) and are conducting it. Until now, our program is fully financed by the École Française d’Athènes but the next workshop should take place on the premises of the Panteion University. The program united both fields and speakers were encouraged to have a comparative approach of their own subject, opening the perspective rather than zooming on specific details, in order to engage all participants.

The day started with greetings by the head of the École Française d’Athènes, Pr. Véronique Chankowski [3], and the responsible for Modern and Contemporary Studies at the EFA, Gilles de Rapper [4], who both placed this research program into the general frame of their insitution’s activities, encompassing the broader region of the Balkan Peninsula and the Eastern Mediterranean, and favouring inter-disciplinary work.

Our key-note speaker was distinguished Pr. Aron Rodrigue [5], born in Istanbul and renowned specialist of Jewish history in the Ottoman domains. The speaker addressed, using the Jewish history, the analytical categories of millet, diaspora, and minorities, which are too often used in an imprecise way and tend to blur empirical phenomena. First of all, Jews did not appear in 1492 in the Ottoman territory. Sephardic Jews were preceded by and contemporary with other Jewish groups in the Ottoman domains. Judeo-Spanish was not a language transplanted from Spain to the Eastern Mediterranean but a language which was organized and formalized on the spot with different and uncoordinated elements from various corners of the whole Iberian Peninsula. The concept of millet obscures perhaps more than helps grasping Ottoman social history. Each millet is perceived as a isolated group, though this could not have been the case. Boundaries were porous and exchanges were daily experiences, even if they alternated with marked separateness. Approaching Ottoman history requires the collaboration of various scholars in order to grasp the different layers of this defunct society, without silencing any group. The Ottoman society was marked rather than by “vivre-ensemble”, by a harsh “antagonistic tolerance” (Robert M. Hayden). The edifice was standing to the benefit of a dominant group, whose tolerance was revocable if their hegemony was endangered. Then tolerance would leave the way to ethnic cleansing. The 19th century experienced the formalization on paper of the millet system, while nationalisms were breaking sown the Ottoman empire, especially on the Balkan peninsula. Antagonisms prevailed over any inherited hierarchical arrangement. What was the role of Ottoman Jews in the new setting? The role of the Alliance Israélite Universelle which became the by-default educational offer of the Ottoman Jews, putting them on the then right in the middle of international stage of economic, social and cultural exchanges, which were taking place in Ottoman cities, pushed them out of their niche as imperial millet, reaching their public even in smaller urban communities – a blind spot in Jewish studies within the Ottoman realm. The heir national states, principally Turkey, would react in reducing them to the status of minority, thus in a clearly inferior place in the new polity.

Pr. Antony Molho [6], who attended the session, emphasized that Zionism was in no circumstance the option of ideological modernization adopted by Ottoman Jews. These characteristics made Armenians and Jews greatly diverge within the Ottoman empire: the former were gained by territorial nationalism while the latter hoped in some local emancipation (such as in the case of Ottoman Salonica) or would favour emigration to the West. Zionism would establish itself in the 1930s and especially after WWII with the assistance of foreign Jewish organizations.

Second speaker was Pr. Giovanni Ricci [7], emeritus from the University of Ferrara. Our colleague attempted to insert Renaissance Italian states and Italian Jews into the history of Ottoman Jewry. The Italian territories were often a necessary station between the Western basin of the Mediterranean and the Ottoman domains, after the completed Reconquista which triggered off the departure of tens of thousands of unwelcome Jews in the from then on only Catholic Iberian peninsula. The conditions were more favorable to Jews in Renaissance Italy, as if the centre of Western Christianity was more benevolent towards them than zealous Iberian Re-conquerors. The trade networks of Venice, Ancon, Ferrara would help Jews establishing links with Ottoman cities like Salonica, Constantinople and Smyrna. The example of la “Señora”, Gracia Mendes Nassi or Beatriz de Luna and her nephew, Joseph Nassi, who escaped threatening Iberia via the Netherlands and finally reached Italy, where Judaism could be openly embraced, prove the importance of Italy in the circulation of Sephardic Jews in Renaissance Europe and their communication with the Ottoman empire, where they established themselves and could play a significant role in Ottoman politics (banking services at the top of the Ottoman society and polity, around Süleyman the Magnificent), international affairs (boycott of Ancona), and Jewish internal affairs (1553, the first printing of a whole Bible in Judeo-Spanish in Ferrare, first attempts of contemporary settlement around Lake Tiberias until 1569).

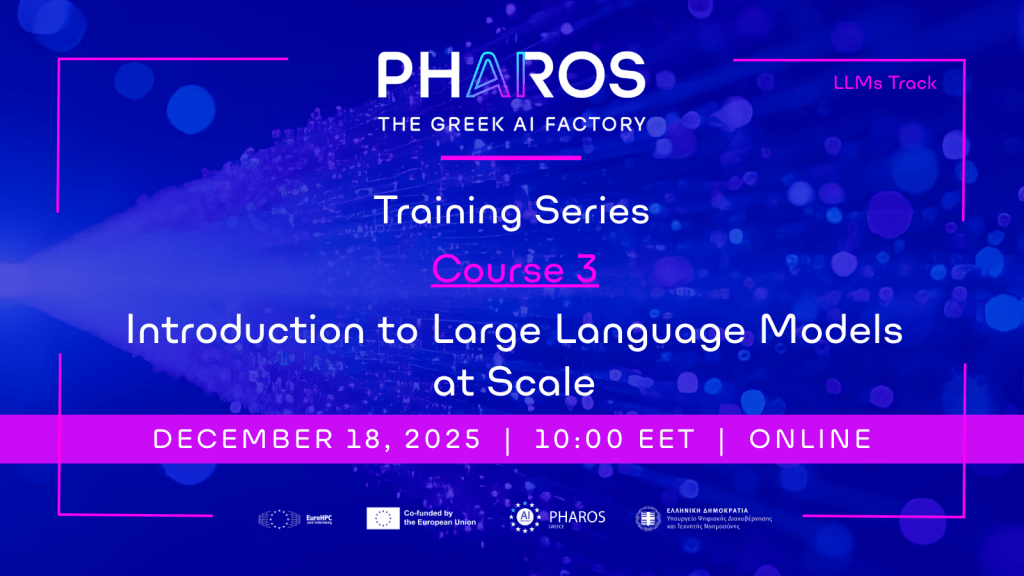

Photographer: Gilles de Rapper

Third speaker was Kônstantinos Takirtakoglou [8], Assistant Professor at the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki. One has to underline that Pr. Takirtakoglou is one of the very few persons in Greece to conduct research on Armenian topics nowadays. Our colleague retraced the singular position of Armenian Cilicia, which evolved from a Byzantine province to a full-fledged Kingdom, recognized by both Rome and Constantinople, in a disputed geographical zone on the frontier of Christian civilization (both Orthodox and Frankish Catholic) and the Islamic world. The territory was not home only to Armenian inhabitants but retained a broader character encompassing Orthodox Christian subjects and Syrian Christians and close contacts with Catholics from the Crusaders’ states (Edessa, Antioch, Jerusalem, etc.) Diplomatic correspondence with Constantinople would take place in any possible language, even in Arabic, which illustrates the non national nature of both polities.

Our fourth speaker was Dr. Vazken Khachig Davidian [9], Associate Faculty Member at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford. Dr. Davidian was born in Cyprus to an Armenian family, is an alumnus of the Melkonian Armenian High School on the island [10], and has been living for decades in the United Kingdom. His main field of expertise is the Armenian visual arts. His presentation focused on the realist production of Ottoman Armenian painters in 19th century Constantinople and how it is to be connected with the progressive agenda of the Armenian élite in the time of broader Ottoman reforms, known as Tanzimat. One of the main issues that Ottoman Armenians had to address was the constant, seasonal or not, migration from the Armenian plateau towards Western Ottoman urban centres, especially Constantinople and Smyrna. Young men would leave their destitute and unsafe province in order to work and earn money, so that they could settle down in their new environment or send help back to their former home village. Dr. Davidian crossed the texts of three Armenian writers in Constantinople, Arpiar Arpiarian, Levon Pashalian and Melkon Gurdjian with the visual productions of Bedros Sirabian, Simon Hagopian and Garabed Charles Nǝshanian, which all focused on the topic and motif of the gurbetçi in Turkish or bantoukhd in Armenian that is the destitute Armenian unqualified worker in Constantinople. Political and aesthetics were intricate and the Armenian learned public could not be spared a confrontation with this issue, while the usual stance of urban Armenians was just despise towards the Armenians from Armenia, Hayasdantsi. (Ironically enough the word today does not refer to provincial Armenians from Turkey but to the citizens of the independent Republic, established outside of any Ottoman territory.) Poverty, filth and health problems were certainly expressed with a touch of romanticism. By contrast, scenes from the inner lands, that is Ottoman Armenia, were represented as healthy, both morally and physically. The important production in visual arts is a characteristic unshared with Ottoman Jews, whose religious prohibitions hindered a similar development in the Ottoman lands, despite the secularization propagated by the Alliance Israélite Universelle.

Our Afternoon session began with Pr. Émilie Themopoulou [11], who teaches at the Department of Turkish Studies and Modern Asian Studies of the National and Capodistrian University of Athens [12]. Our colleague based her presentation on her intimate knowledge of Ottoman archives, especially of fiscal nature in order to examine the social and economic changes experienced by the Jewish population in Salonica at the end of the 19th century, which happened to be the end of the Ottoman sovereignty on the city. The independence of the first contemporary Greek state favoured the Jewish subjects of the Sultan, who dominated demographically the port-city. These were playing a major role as suppliers of stuff and uniforms for the Ottoman army, but also as traders between Italy, Austria, France, Great-Britain and the Ottoman domains. The types of occupations exerted by Jews became more diverse with the surge of liberal professions and the development of industrial productions (food industry, tobacco manufactures, spinning mills), for instance. Internally, the community experienced new forms of solidarity with the intervention of rich individuals in favour of destitute Jews, whose number would not regress. Benevolence and charities were essential for the maintenance of some social equilibrium within the community and in the city at large. Dr. Moïse Alatini would not only subsidy Jewish schools but Greek ones too. The Alliance Israélite Universelle would accept non Jewish pupils. The Jewish community would remain a poor one on the whole. Some 6 or 7 % could be considered as really well-off. The community-based organizations would concern only 10 % of the Jewish populations when elections were organized. The idealized, now forever gone, Madre de Israel, was a polarized society.

Our sixth speaker was Lida Dodou from the University of Vienna, where she is a PhD candidate. Her presentation dealt with the Salonica Jews migrating to Austria-Hungary, a topic which has remained largely under-researched because of more obvious links between Salonica Jews and Italy or France. However migrating to Austria-Hungary was a seducing possibility because of the legal equality granted to all subjects of the Emperor in 1867 and thanks to the direct railway connection with Vienna from Salonica which was established in 1888. Generally speaking, the influence of the double monarchy in Salonica should not be underestimated. While in 1767, not one Austrian vessel would enter the harbour, in 1892 most ships coming to Salonica would belong to Austria. This development could take place only with the cooperation of the city’s Jewish population. With the economic ties, the Austrian protection and then naturalizations would expand among the Jewish population. Salonica would export Sephardic Jews to Vienna, where a Türkish-Jüdische Gemeinde zu Wien would be set up in 1867, and where a Sephardic synagogue would be erected in 1887, in the Zirkusgasse. The definite emigration would start mostly after 1912. Some Jews would prefer to remain in an imperial frame rather accommodating with the Greek national state. The Austrian Jewish community accepted little by little the newcomers. Antisemitism was dominant in Vienna (Karl Leuger, the mayor, was a vociferous enemy of the Jews) and may explain why Salonica Jews would rather settle down in other places. The mobility of Salonica Jews may explain why many of them established in the former double monarchy would escape the Shoah, unlike their coreligionists who remained in Greek Macedonia.

I was the seven speaker of the day. I made a presentation about the pre-Diaspora aspects of Smyrna Armenians during the long 19th century in the Ottoman empire. I recalled the subsequent waves of settlement of Armenians on the Aegean shore, a place considered as home but distinctly outside of Armenia, whatever its geographic (arduous) definition. Away from any Armenian soil, refugees from Cilicia, Caucasus (Nakhichevan), Persian-Ottoman war zones (Isfahan), Ottoman inner provinces would seek and find in Smyrna a safe haven. Gurbetçi would settle down in Smyrna, carrying with them the discontentment of destitute rural populations from Erzurum, Kayseri, Tokat, Bursa and Manissa. The existence of caravans and then of a railway network centred on Smyrna made these inner migrations increasingly easy. In the same time, Armenians would easily emigrate from Smyrna – boarding a ship was an everyday possibility – to Alexandria, Manchester, Marseilles, and Paris, for instance. Therefore, emigration and mixed marriages outside of the community boundaries could explain why the number of Armenians remained only stable in this period. Smyrna would be concerned by the spread of new political ideas: the ideal of the nation would reach this urban and remote population. The local community would sustain educational facilities (both Pre-Chalcedonian and Catholic), a press (i.e., Oriental Press) and publishing houses (for instance: Dédéyans’) which would re-shape Armenian modernity, attract the interest of Armenians elsewhere and expand the public concerned by “national” issues. Smyrna would be addressed after 1922 by monographers and take place in form of memorial books on the shelves of Armenian library around the world. Interest would be renewed on each anniversary of September 1922 either in Armenian or in the languages of host-countries.

Last but not Least, Dr. Tacoui Vakirtzian, free scholar, who received her PhD of art history in Paris, and studied Armenian philology at the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales [13], based in Heraklion, her city of birth, made a presentation about the Armenian presence in Crete from the Ottoman conquest to 1913. Dr. Vakirtzian has ample access to Armenian sources in Candia [14], and elsewhere and crossed these sources with Ottoman material, located in Crete or, for instance, at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris [15], with the help of Pr. Ilias Kolovos [16]. Similar to a detective, Dr. Vakirtzian could trace individuals settled on Crete by the Ottoman rulers, especially in order to reconstruct Candia (1669). Miners and masons were especially needed in this context. The community experienced a diversification: bakers, hat-makers, jewelers, bankers, and merchants would appear in the sources. A Greek-Orthodox church was bought by the community and transferred to the Armenian cult (1773). It turned to the centre of the Armenian community in Candia. Armenians were close to the Ottoman power and could work, for instance as defterdar, in Crete. Armenians would keep on travelling around the Ottoman Mediterranean and facilitated financial exchanges between Crete and other places, and between Cretans of different creeds.

by Hervé Georgelin (Département d’études turques et d’études asiatiques contemporaines, Université nationale et capodistrienne d’Athènes) – Member of the Organizing Committee

On the left: Émilie Thémopoulou, Lida Maria Dodou, Giovanni Ricci, Tacoui Vakirtzian (the furthest)

On the right Vazken Khachig Davidian, Aron Rodrigue and visitor Arshalouys (the closest)

İn the evening, a well-deserved dinner at Γιάντες, offered by the EFA.

Photographer: Hervé Georgelin

[1] http://www.turkmas.uoa.gr/an8ropino-dynamiko/melh-dep/herve-georgelin.html

[2] https://www.linkedin.com/in/odette-varon-vassard/?locale=fr_FR

[3] https://www.hisoma.mom.fr/presentation/annuaire-du-personnel/chankowski-veronique

[4] https://www.idemec.cnrs.fr/spip.php?article226

[5] https://history.stanford.edu/people/aron-rodrigue

[6] https://www.eui.eu/people?id=anthony-molho

[7] http://www.stmoderna.it/ricci-giovanni-giuseppe_s284 [8]https://olympias.lib.uoi.gr/jspui/bitstream/123456789/28027/1/%CE%94.%CE%94.%20%CE%A4%CE%91%CE%9A%CE%99%CE%A1%CE%A4%CE%91%CE%9A%CE%9F%CE%93%CE%9B%CE%9F%CE%A5%20%CE%9A%CE%A9%CE%9D%CE%A3%CE%A4%CE%91%CE%9D%CE%A4%CE%99%CE%9D%CE%9F%CE%A3%202017.pdf [9]https://www.orinst.ox.ac.uk/people/vazken-khatchig-davidian

[10] https://nonument.org/nonuments/melkonian-educational-institute/

[11] https://www.cairn.info/revue-bulletin-de-l-institut-pierre-renouvin1-2015-1-page-139.htm [12] http://www.turkmas.uoa.gr/fileadmin/turkmas.uoa.gr/uploads/cv_neo/251022_THEMOPOULOU_VIOGRAFIKO.pdf

[13] http://www.inalco.fr/langue/armenien

[14] https://www.neakriti.gr/article/politismos/1543367/350-hronia-apo-tin-idrusi-tis-armenikis-ekklisias-sto-irakleio/

[15] https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr et https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc4355v

[16] http://www.history-archaeology.uoc.gr/to-tmima/didaskontes/ilias-kolovos/